In 1931, Josiah Kirby Lilly assembled a staff of researchers and librarians to acquire early and first editions of sheet music of all of the music of composer Stephen Collins Foster (1826-64).

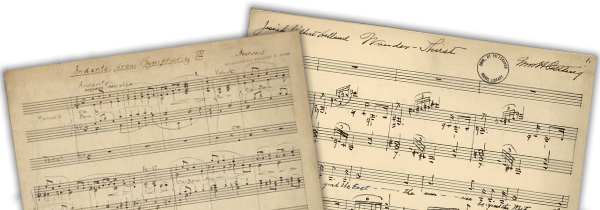

With the Foster Hall Collection nearly complete in 1933, Lilly turned his attention to creating a complete facsimile edition, known as the Foster Hall Reproductions. As stated in the May 1934 issue of the Foster Hall Bulletin, the Reproductions were printed on "specially made rag paper ... placed in three thousand hard buckram, dust proof, slip cases and one thousand steel shelf containers." Lilly shipped 1,000 copies to libraries around the world, free of charge.

Foster Hall indicated that their goal was to immortalize Foster's music: "The object of this endeavor is to place in reference libraries sets of these faithful reproductions as a permanent record of the work of America's greatest composer of beautiful melodies, many of which are, and deserve to be, immortal." Lilly wrote that the Reproductions were designed to "remain intact for several hundred years if not victim of fire or accident," and that they "are intended to be one of Foster Hall's important contributions to a better knowledge of Stephen Foster."

Lilly and Foster Hall's actions were not as objective as they might seem. In the United States, Foster's star had dimmed considerably at the end of his life. For three decades after his death, only a handful of his sentimental minstrel songs--especially "Old Folks at Home," "Massa's in de Cold Ground," "My Old Kentucky Home," "Old Black Joe," and "Uncle Ned"--survived in public consciousness. The decline of Foster's music in the United States began to reverse course in the 1890s, and Lilly emerged as Foster's greatest champion in the 1930s. Lilly's aim was to establish Foster, once and for all, as an American icon.

In doing so, Foster Hall had to navigate divided public perceptions of the composer. Many Americans thought of Foster as a composer of sentimental "heart songs" and "negro folk songs." Many others, however, viewed him as a composer of songs that sentimentalized white supremacy. Both views had supporters and detractors, and divisions were not easily navigable. Whites, blacks, progressives, radicals, conservatives, and white supremacists all split, coming down on different sides of the debate.

Foster Hall could not erase race altogether from Foster's music, for the overtness of race in songs such as "Old Black Joe" is precisely what many listeners--white and black--loved about the songs. Instead, Foster Hall attempted to defuse controversy by minimizing race. They hired white and black musicians to perform and record Foster's music, and they acknowledged but did not dwell on Foster's personal opposition to the abolition of enslavement. Overall, they subsumed his songs' with ties to blackness within a discourse of universalism. In the introduction to a book of Foster's music for school children, Foster Hall wrote, "The songs are simple and lovable, and they belong to the whole world; for all hearts are alike in feeling tenderness, merriment, joy, sympathy, and love of home, and must have some beautiful way of expressing feelings, such as we find in song" (emphasis added). In other words, when framing Foster's music, Foster Hall made a choice to focus on the admirable human emotions often expressed in the songs, not on the racial identities and stereotypes Foster often overtly depicted.

Foster Hall's objective is best understood, therefore, as seeking to establish the composer as an American icon by minimizing and subsuming race within ideals that transcended race. The Foster Hall Reproductions were part of this. By publishing Foster's complete works for the first time, the Reproductions clearly demonstrated that Foster's racialized songs comprise less than one tenth of his output. And by printing only basic bibliographical information, Foster Hall eschewed having to address the composer's close ties to blackface minstrelsy and the outsized influence of his minstrel songs on his success and fame.