WARNING: This is a blackface minstrel song, a genre that features demeaning caricatures rooted in racism and white supremacy.

“Old Folks at Home” was submitted for copyright entry on August 26, 1851, and copyright deposit on October 1, 1851, by Firth, Pond & Co. Despite the title page attribution that the song was written and composed by E. P. Christy, Stephen Foster wrote the words and music for “Old Folks at Home.” Minstrel performer E. P. Christy paid Foster $15 for the privilege of having his name as composer of “Old Folks at Home,” apparently at Foster’s suggestion. The composer wrote to Christy on May 25, 1852, requesting a cancellation of this arrangement because, as Foster put it, “I wish to establish my name as the best Ethiopian songwriter. But I am not encouraged in undertaking this as long as ‘The Old Folks at Home’ stares me in the face with another’s name on it.”

In the 1890s, Czech composer Antonín Dvořák arranged “Old Folks at Home” for for soprano, baritone, choir, and orchestra. This arrangement was premiered in New York on January 23, 1894, at a benefit concert organized by the city’s National Conservatory; the concert was conducted by Dvořák himself.

According to Evelyn Foster Morneweck’s The Chronicles of Stephen Foster’s Family:

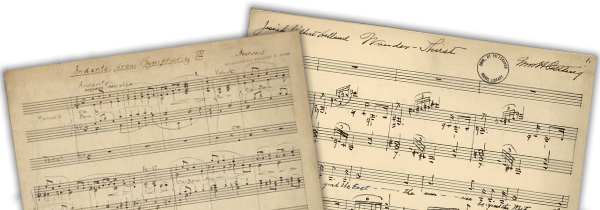

During the summer of 1851, he had composed two negro melodies which certainly did not require his residence in the deep South to make them beautiful and appealing to every heart, North or South. “Oh! Boys, Carry Me ’Long” was copyrighted on July 25, 1851, and “Old Folks at Home,” on October 1. Concerning the latter song, Morrison tells this story. He was working one day at his desk in the Hope Cotton Mill, when Stephen came into his office and said, “What is a good name of two syllables for a Southern River? I want to use it in this new song, ‘Old Folks at Home.’” With a laugh, Mit asked him, “How would Yazoo do?” referring to a comic song of the day, “Down on the old Yazoo.” Steve replied, “Oh, that’s been used before!” It was hard to think of a river in the South with a name of only two syllables, and all that Mit could offer further was Pedee. Stephen snorted, “I have that, and it doesn’t sound right.” “Well, here’s the atlas, let’s have a look at it,” said Morrison, lifting it down from the top of his old brown desk. They both pored over it, and Mit’s finger stopped at Suwannee, a little river, with its source in Georgia, flowing through the state of Florida to the Gulf of Mexico. “That’s it, that’s it exactly!” exclaimed Stephen with delight, as he crossed out the ridiculous Pedee and wrote in the other name. The song was finished. It commenced “Way down upon de Swanee Ribber.” Then, he left the office, as was his custom, abruptly, without saying another word, and Mit resumed his work. Thus, just as Stephen changed it that day, with the name Pedee blocked out and Swanee written above it, the original draft of “Old Folks at Home” appears in pencil in Stephen’s manuscript book, now preserved in the Foster Hall Collection at the University of Pittsburgh. ...

At this time, Stephen had an agreement with E. P. Christy to allow Christy the privilege of singing Stephen’s songs prior to publication. For the privilege of first singing “Oh! Boys, Carry Me ’Long,” “Massa’s in de Cold Ground,” “Old Dog Tray,” and “Ellen Bayne,” Christy paid Stephen ten dollars for each song; this also included the right to have printed on the cover page “As sung by E. P. Christy,” or “Christy’s Minstrels.” For “Old Folks at Home,” and “Farewell, My Lilly Dear,” Stephen received fifteen dollars each. That there was quite a friendly relationship between Stephen and E. P. Christy at the beginning of this arrangement is evidenced by two letters from Stephen that are preserved in the Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, California. [Correspondence is linked below]

Mr. Christy lost no time in accepting Stephen’s offer. The latter’s next letter is dated June 20, 1851; in this, Stephen shows that, as a composer, he was very particular about the way his works were presented to the public, and was anxious that the mood that attended the writing of “Oh! Boys, Carry Me ’Long” should be shared by the singer. [this letter is linked below]

After the publication of “Old Folks at Home,” the cordial feeling between Stephen and E. P. Christy appears to have become strained. For some reason, Stephen’s publishers seemed to think that it was better for Stephen to build up a reputation as a writer of refined, sentimental white songs, than as a writer of Ethiopian melodies, though his compositions in the latter class were more popular and were superior to the other sort. Doubtless the publishers were influenced by the attitude of several “high-class” musical journals which had joined in a common disparagement of negro melodies. Stephen unthinkingly suggested to Christy that he allow his, Christy’s, name to appear on the title page of “Old Folks at Home,” as the composer. It was the last time that Stephen ever did anything so foolish. “Old Folks” was an instantaneous and overwhelming success and, as Stephen regretfully said, stared him “in the face with another's name on it.” Regretting the injudicious transaction, Stephen wrote to Mr. Christy the following letter on May 25, 1852. [this letter is linked below]

The foregoing letter is reminiscent in many ways of the naive epistle Stephen sent as a boy to Brother William, explaining in detail why it was so necessary that he, Stephen, should leave Jefferson College. The letter to Christy reveals the same ingenuous and juvenile reasoning of the fifteen-year-old homesick Stephen. The fact that he was placing Mr. Christy in a very embarrassing position did not seem to occur to the composer of “Swanee River.” Christy had been showered with praise every time he sang what was supposed to be his own beautiful song; he was now asked to turn about face and admit that he did not deserve this adulation, and that he had paid to have his name published as the author of another man’s composition. When Morrison Foster wrote his Biography of Stephen C. Foster, he stated that Christy had paid Stephen five hundred dollars for the privilege of placing his name on the music as author. He must have received this information from Stephen. Morrison opposed this foolish piece of business from the start, for he saw no fault in Stephen’s negro melodies, and felt Stephen should be proud to own them. In a letter written March 13, 1889, to Monroe Crannell, of Albany, New York, Morrison tells something about the matter:

“I was cognizant of all the facts at the time, of my brother’s giving his consent to Christy’s name appearing on the first edition of the Old Folks at Home, and sang the song at home many times before Christy ever saw it. I reasoned against giving the permission, but not succeeding, I prevailed on my brother to require Christy to sign the written disclaimer, which I drew up myself. Christy did so, and my brother then sent the manuscript to Firth Pond & Co. his publishers, and authorized them to print Christy’s name on it.”

Stephen’s request that his own name be permitted to appear on subsequent editions of “Old Folks at Home” was refused, and on the back of Stephen’s letter, Mr. Christy made note of his opinion of his friend, Stephen C. Foster, which was that Stephen was mean and contemptible, and a vacillating skunk and plagiarist! Vacillating Stephen might have been, but the other most undeserved epithets seem to have been prompted by furious resentment rather than usual fairness on the part of Christy. Nevertheless, in spite of Christy’s name on the title page, in a short time it became well known that Stephen was the true composer of this great plantation melody, and the next year, 1853, Firth, Pond & Company listed it amongst “Foster’s Songs” in their advertisements. All his life, however, Stephen was compelled to see “Swanee River” sold over the music counters bearing the inscription “Written and Composed by E. P. Christy.” Although all the royalties were paid to Stephen it was not until the copyright was renewed in 1879 by Morrison Foster for the benefit of Stephen’s widow and daughter Marion, that full credit was given on the title page, and in the Copyright Office, to Stephen C. Foster as composer of this, one of his greatest songs.

In the Appendix she notes:

The Suwannee River rises in the Okefenokee Swamp of southern Georgia and flows through northern Florida to the Gulf of Mexico. This river is immortalized in Stephen Foster’s great song “Old Folks at Home” (“Way Down Upon the Swanee River”). The state of Florida and its citizens are proud of the song and its composer. They have, accordingly, established a number of memorials to Stephen Collins Foster. “Old Folks at Home” (“Way Down Upon the Swanee River”)—state song of Florida—Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home,” composed in Pittsburgh in 1851, was selected as the official state song of Florida by the Florida Legislature, May 28, 1935, in House Resolution No. 22. The bill was sponsored by S. P. Robineau, member of the Legislature from Dade County.